by Tim Eldred

As I write these words, over 20 years have passed since the idea first crossed my mind to write and draw comics about a gorilla in space. In all that time, the thing has never left my side, even when I neglected it. For anyone who likes a tale about the flow of ideas or the rewards of unswerving dedication, here is the story in full. None of the names have been changed, and no one is innocent.

Phase 1 (early 1990s)

It all started on a tiny little creative whim and a great big throbbing pustule of righteous anger.

The whim was this: to create a fun little comic strip about a diverse cast of non-super-powered characters finding their way through life. The anger came from the comic book industry’s lack of concern over the need for such comics – and its occasional hostility toward the very idea of them.

It was 1992, and the future didn’t look promising. More and more of the same old stuff was coming down the pike. More rage-filled superheroes, more soft-core Amazons, and more of the same junk that didn’t appeal to the mainstream public. It was always my feeling that this industry would stagnate if it didn’t work harder to broaden its readership, and it often seemed like I was alone in my concern. What was to be done? Well, everything starts with an act of creation, and as a comic book creator I felt it was my responsibility to come up with something to address this need.

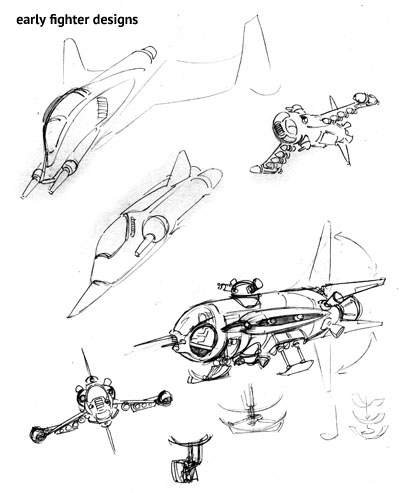

So where did Grease Monkey come from? Several places. First, I’d always loved outer space SF action, so that was my backdrop of choice. Second, I’ve always had a respect for well-crafted war stories. War, like love, forces people to dig deep into themselves and learn the true source of their humanity. Against this tapestry, you can learn a lot about what makes us tick.

The thing about war, though, is that increasingly few of us have actually experienced one, so its value as a reference point is slowly eroding. For writing to endure and find a wide audience, it needs something universal and relevant to our daily lives. Therefore, I started thinking about the role of non-combatants – people living in a wartime environment, but not constantly placed in life-and-death situations. The non-combatant’s life is beset on all sides by bureaucracy, personal politics, stifling regulations, and emotional conflict – not unlike the lives of us “normal” people.

I’d been kicking around this notion for a few years, looking for a way to focus it, when inspiration came from a Stan Ridgway song called Overlords. The narrator of this song was a man laboring under alien domination, dreaming about going underground and “monkeywrenching” for the resistance. This is a term for acts of sabotage, but it also planted the image in my head of a battlefield mechanic whose job it is to keep the machines running. This was a character I could work with.

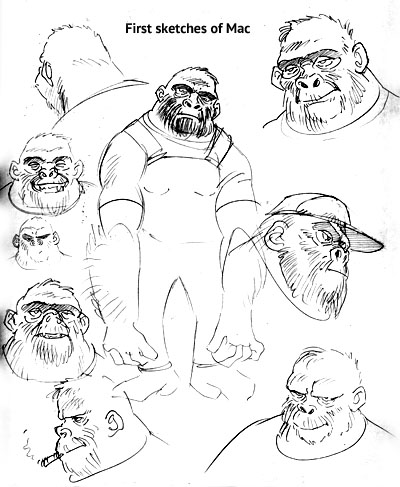

Still keying off the word “monkeywrenching,” I wondered what it might be like if the character were a gorilla. (Because, of course, as everyone knows, gorillas are the coolest animals on Earth.) That lit the fuse for everything that has happened since.

The next step was to decide where the gorilla came from and how he found himself among humans. I wrote an extensive backstory to explain this, which I’ve tinkered with over the years, to be revealed as the bits and pieces become relevant.

In choosing the setting for the story, I decided to place it inside a spaceship, a giant pressure cooker. And there would be many gorillas working alongside humans, not just one. A whole culture was beginning to form, in which the idea of a diverse cast expanded from gender and race to include a whole separate species. The possibilities for tension and conflict expanded right along with it.

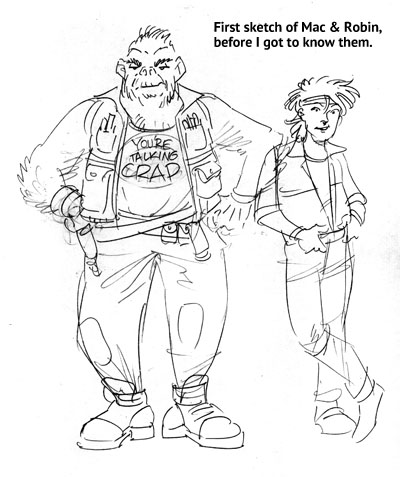

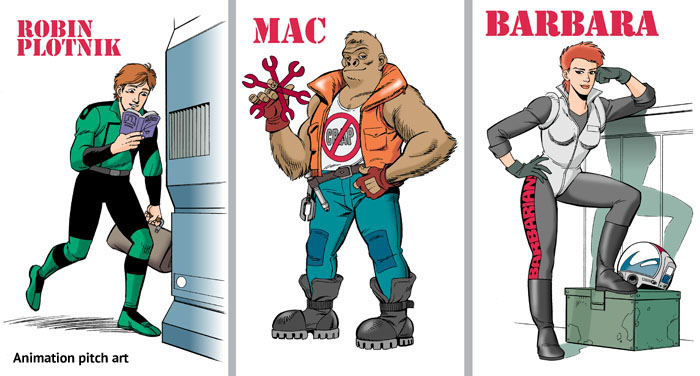

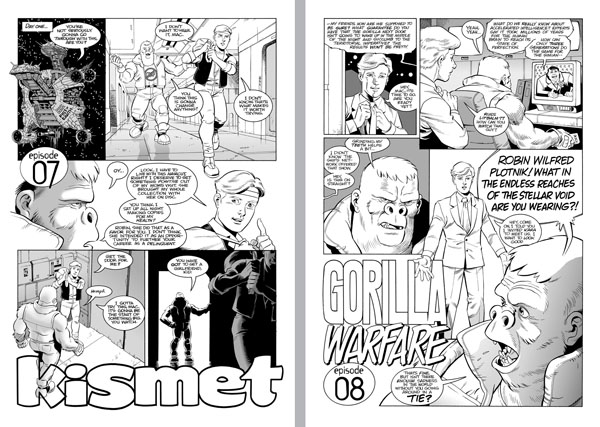

The idea was getting complex enough now require a human focal character who would be immersed in this culture on behalf of the reader. To my surprise, that character turned out to be me. Robin Plotnik is exactly who I saw myself as most of the time, at least back in 1992; a hopeful, optimistic, well-meaning young buck who thinks he’s got it all figured out but is in for a lot of surprises. Robin’s personality and his reactions to things are much more like mine than I first intended, and I was utterly blind to this until other people began pointing it out later on. Once it became clear, the purpose of the project took on a whole new meaning.

I put a few more pieces into place and created the first episode, Art Lovers, in the summer of ’92. (See the liner notes for more detail.)

What continues to amaze me the most about Grease Monkey is the wealth of unexpected rewards it has brought my way. I should explain that I’ve always been a staunch advocate for the creative impulse. Whenever talking with beginning artists who want to draw comics for a living, I always make it a point to value originality and self-determination. Traditionally, the measure of true long-term success comes from how unique your vision is, not how well you follow someone else’s lead. To that end, I advocate that instead of waiting around for a big break, artists should look for ways to satisfy their own creative goals on their own time and use their freedom to their advantage (before it gets overtaken by deadlines).

Anyone who wants to see the value of this approach need look no farther than Grease Monkey. When I started, it only existed for an audience of one: me. I took time off from paying projects just to entertain myself with it. I knew one day I’d offer it to a publisher, but my primary purpose was to have the simple joy of creating it. I didn’t know then that when you risk a break from the daily routine to pursue your dream, you place yourself in the hands of fate, and there’s no telling what fate has in store.

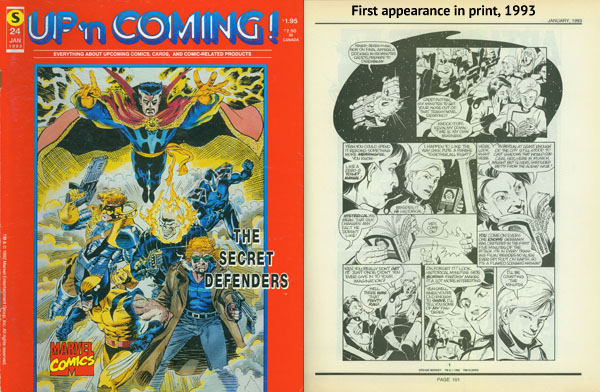

So imagine my surprise when this happened: a few days after I finished drawing the first episode, I contacted a Canadian comics distributor, Styx International, on an unrelated matter and out of the blue they asked if I had anything new they could publish in their magazine, Up’N’Coming. As a matter of fact, I did. A few more days later, the deal was done.

Editors Joe Krolik and Brent Richard loved the first strip and immediately hired me to come up with five more. Fate had rewarded me for taking a chance. And this was only the beginning.

Writing and drawing these six episodes carried me into 1993, by which time I’d moved across the country from snow-locked Michigan to sunny Southern California. This put me a lot closer to Hollywood, the magical kingdom where anything goes…

Phase 2 (mid 1990s)

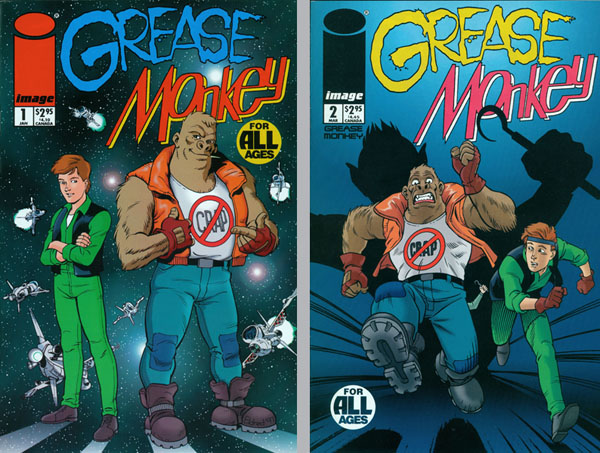

A year passed, and in the spring of 1994 I found myself at an industry convention in the presence of Denis Kitchen. I’d always respected Denis’ company, Kitchen Sink Press, and was intrigued by the transformation of Mark Schulz’ magnificent Xenozoic Tales into the highly-underrated Cadillacs and Dinosaurs cartoon for CBS. This seemed like an ideal blueprint for Grease Monkey, so I approached Denis about publishing it as a regular series. To my delight, he asked me to colorize the six existing strips, and KSP would collect them into two standard-format comic books. Getting a second lease on life was amazing enough, but having the chance to go back and upgrade the strip was quite a bonus.

Grease Monkey #1 and #2 came out from Kitchen Sink Press in early 1996, and though they didn’t quite set the world on fire, they did open the gate into the world of animation via Kitchen’s Hollywood rep, Brad Neufeld. Developing the strip for animation turned out to be a thoroughly eye-opening, occasionally frustrating, and infinitely educational experience. I gained a front-row view of what TV execs insisted was appropriate for children and acceptable to sponsors. I won’t disgust you with the details just now. Suffice to say, the cart often came before the horse and the tail nearly always wagged the dog.

Nevertheless, this experience too handed me an unexpected reward. The Neufeld connection put me together with an animation writer (Jymn Magon), an agent (Ellen Vein), and ultimately a career in the cartoon biz. In the fall of 1995, Grease Monkey was pitched as an animated TV series to several networks and studios, including MCA/Universal. Producer Ralph Sanchez took a shine to it, particularly the artwork on my presentation boards, and he offered me a job on a series in development called Wing Commander Academy (based on a PC game starring Mark Hamill).

The timing couldn’t have been better. Things were getting rough in the comics industry because not enough had been done to broaden the audience (ah, you could cut the irony with a knife), and animation was the next logical stomping ground. I didn’t have any practical experience in animation storyboarding, but Ralph and Universal took a chance on me anyway, and I didn’t let them down. I ended up storyboarding several episodes of WCA and serving as a character designer for the series during the summer of 1996. The show debuted on USA Network that fall, and it gave me my first official screen credits.

This led directly to a gig at Columbia/Tri-star TV animation. I began as a storyboard artist there at the end of 1996, but one look at Grease Monkey convinced producer extraordinaire Audu Paden that I had the chops to be a director. In very little time, I found myself helming several episodes of Extreme Ghostbusters, which premiered in September 1997.

Phase 3 (late 1990s)

In the summer of ’96, Ralph Sanchez had moved from Universal to Film Roman (home of The Simpsons) and engineered a development deal there for Grease Monkey. This meant developing new concepts for a TV series, and it inspired me to write some new comics. In the space of a few months, I cranked out 18 new stories, bringing the total up to 24. I’d intended to start drawing them right away, but with a full-time job in animation my plate was pretty full. Regardless, more rewards appeared anyway. And this time, they were far more valuable than jobs or money.

Something happens when you place yourself into your own works of fiction, as I unwittingly did with young Robin Plotnik. When your characters are extensions of you, and react to things as you would, it puts you in a rather godlike position. Writing the new stories gave me that experience. When I put Mac and Robin through one crisis after another, it was up to me to work out the solutions to their problems. Unwittingly, I was writing myself a manual for crisis management.

This manual, such as it was, gave me a vital reference point throughout 1997, as I faced trials in my personal life that I wouldn’t have been equipped to handle at an earlier time. This brought me a nice revelation: that not only does life imitate art, my life was imitating my own art. For practically everything that happened to me, I could find some parallel in a Grease Monkey story. In other words, I’d already faced these crises on paper. The chance to live one’s own art must be one of life’s greatest rewards, and all it took was the resolve to break with routine back in 1992. But it wasn’t over yet – not by a long shot.

Something else that happened in ’97 was a surprise connection with Image Comics. Like everyone else in comicdom, I had watched the rise of this aggressive publisher with interest. I had not, however, found much to interest me in their actual comics, which seemed intent on treading where others had already gone. So when my friend Kurt Busiek (writer of such magnificent comics as Marvels and Astro City) recommended that I approach Image’s editor-in-chief Larry Marder with Grease Monkey, it seemed slightly insane. When Kurt told me that there was more to Image than I originally thought, I took his word for it – and damned if he didn’t turn out to be right.

Marder put me in touch with one of the Image principals, Jim Valentino, who was just as passionate as I was about broadening the readership. He had turned this passion into his own sub-group of black & white comics that followed the tenets of DIY creator ownership…but with the Image Comics logo on the cover. This was an idea I could warm to.

Jim was impressed with Grease Monkey, and in a few short months the original stories saw their third time in print (spring 1998). Despite critical acclaim, the sales figures were barely high enough to cover the printing costs, so the series fizzled out before I could begin drawing the 18 stories that were lying in wait.

Disappointing, yes, but not discouraging. There was much still to do. The rest of 1998 and most of 1999 was filled up with work on a graphic novel, which was yet another of the many rewards. Let me back up again to 1992 for an explanation. At about the same time I was working on the first six episodes of Grease Monkey, author Daniel Quinn published a revolutionary novel called Ishmael. Daniel and I had something remarkable in common; the main characters in both our stories were talking gorillas. When I heard about Ishmael, I devoured it instantly and found it to be one of the most amazing books I’d ever read. I contacted Daniel to say hello, and sent him some Grease Monkey comics just for laughs. What I got back was an offer to work together.

Daniel has written a lot of books along the lines of Ishmael, all dealing with the heady subject of where our species is headed. He’d also written a screenplay in this vein called The Man Who Grew Young. It didn’t look as if it would get made into a film, so Daniel asked if I’d be interested in turning it into a graphic novel instead. I thought about it for approximately three seconds and that was that. I’ll cut to the chase and say that The Man Who Grew Young was published by Context Books in the summer of 2001, and I’m immensely proud of it. All the while I was working on it, I vowed that afterward I would return my attention to Grease Monkey and finally start drawing those later episodes. I managed to fulfill half of that vow. I would indeed return to Grease Monkey, but not in the way I’d planned.

Phase 4 (2000 plus)

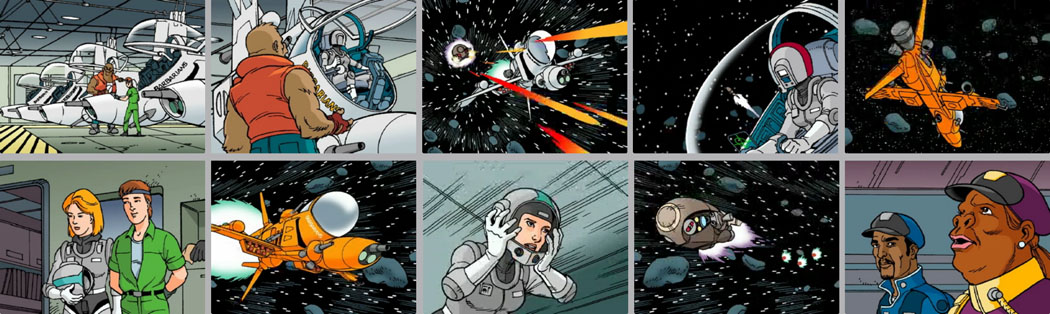

1999 was drawing to a close, and a brainstorm had struck. By day, I was still working in TV animation, and I had gained a lot of skills since ’96. One part of the process of making cartoons is to assemble the storyboards and voice tracks into an animatic – a sort of slideshow that served as a blueprint for the finished program. Technology had reached a point where animatics could be assembled on a home computer. Hence, the brainstorm: why not make a Grease Monkey animatic and use it to pitch the series again for TV? I had everything I needed, including friends who could supply the voices. The only thing I lacked was a sense of what a monumental undertaking it would be.

In the fall of 1999 I wrote a script for a Grease Monkey pilot film entitled All You Need is Love. I thought it would run about 5 minutes and I could make the whole animatic – start to finish – in a month or two. The script actually timed out to about 7 minutes, so I figured maybe three months. Then I started drawing and the thing just kept growing. The more I worked on it, the more I added. I also decided to do it in full color, which meant even more production time. In the end, it required over 2,000 drawings, took 6 months to make, and totaled 17 minutes of screen time…just 5 minutes shy of a standard made-for-TV episode. But it was so much fun, I had to make another one!

The first cartoon wrapped in July 2000 and a month later I got going on a second short entitled Black Holes Suck. It was more fully animated than the first film, and although it totaled only 6 minutes, it took another 6 months to finish. It became obvious that I couldn’t do this for a living, but I got the job done – both of these animated visions really exist! Now I could march into a Hollywood studio, shove a tape into a VCR, and say “look – here’s my show!” Did it work? Of course not. Why? Lousy timing.

The first time I pitched Grease Monkey, the animation industry was pretty unstable. A lot of studios were being bought by other studios, or management was changing, or execs were just too scared to start anything new. The year 2000 was also pretty unstable. The TV animation biz was shrinking again (it does this every 10 years or so) and everyone wanted goofy slapstick shows like the ones that were successful the year before. I tried internet companies, but they only wanted adult (i.e. shock-humor or soft-porn) cartoons. Once again, Grease Monkey was a misfit. The odd thing was, everyone outside Hollywood loved my cartoons and wanted more. The guy who said “nobody in Hollywood knows anything” must have gone through something like this.

One more thing occurred during the whole cartoon-making experience. Thinking that Grease Monkey could also be pitched as a feature film, I decided to write a screenplay for one. This was easier than it sounds, since I already had the mini-bible from 1996 to fall back on. The 17-minute pilot film worked perfectly as an opening act, so I just took off from there and started writing. This took about a month, and in late July of 2000 I finished a 95-page first draft. I debated whether to turn it into either a long-form animatic or a graphic novel, but there were other things to do first. To be precise, there were 18 other things to do first.

In January 2001, I finally started drawing Grease Monkey comics again. Having all those scripts sitting in reserve was often a great comfort in previous times, like having a dresser drawer full of warm socks. I’d often heard that “real” writers had an archive of unpublished work sitting in their files to be discovered after they die, so for that brief time I felt like a “real” writer. (In fact, after I started drawing again I occasionally thought I might not live long enough to finish. Fortunately, this turned out to be simple dementia.)

In January 2001, I finally started drawing Grease Monkey comics again. Having all those scripts sitting in reserve was often a great comfort in previous times, like having a dresser drawer full of warm socks. I’d often heard that “real” writers had an archive of unpublished work sitting in their files to be discovered after they die, so for that brief time I felt like a “real” writer. (In fact, after I started drawing again I occasionally thought I might not live long enough to finish. Fortunately, this turned out to be simple dementia.)

For reasons that were entirely aesthetic, I decided to continue with the 12-page episodic format that I’d established in the very beginning. Because of this, there was always a charge of anxiety during the first step, where I broke each script down into thumbnail sketches. I placed a rigorous 12-page rule on myself, and like all rules it was bound to be broken. Some stories contained themselves effortlessly. Others fought like demons. The first time I allowed myself to break the rule (on episode 11), all bets were off. So much for discipline.

An interesting aspect of the whole creative process is the transfer of importance from one stage to another. Every story makes its way through script, thumbnail, rough layout, pencil, ink, and printing. Whatever stage I’m on at any given time is the most important. For a while, the script is indispensable. When I finish the rough, the script is old news. By the time I get to the inking, the rough is waste paper. When these things were merely hypothetical, they were priceless. Now that there’s a finished product, they’re just taking up space. Following this premise to its natural conclusion, the end product is just the transient vehicle of an idea. What you’re reading here is less important than the ideas it communicates. If I got it right, the ideas will resonate for a good long time and the comics themselves can vanish. (Not that I want them to, of course…)

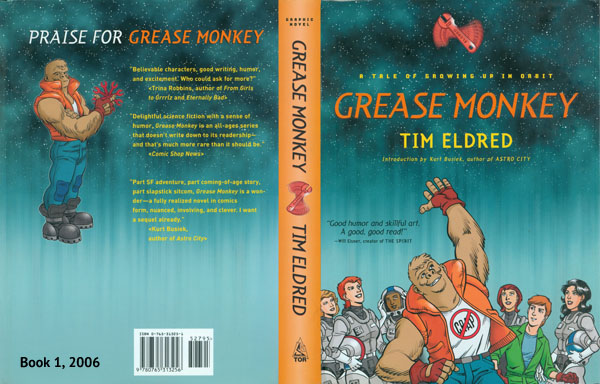

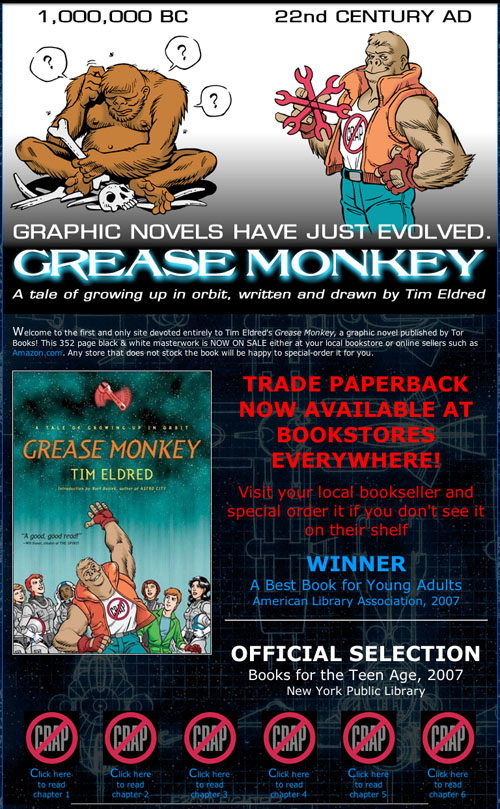

By now it should be obvious that getting this work done was quite an undertaking, with a full thirteen years having passed since the start. Book 1’s final phase began when all 24 chapters (plus three vignettes) were finished in 2002, and I decided to approach a book publisher outside the comic book world. This required the support of a canny literary agent named Ashley Grayson, who received my introductory letter at precisely the same moment he thought about adding a graphic novel to his already impressive credentials. Ashley suspected that Tor Books might feel the same way, and about a year later his hunch paid off.

From there, my editor Teresa Nielsen-Hayden took me under her wing and pulled me into this entirely new realm. She knew it would be a challenge, since the production leap from prose fiction to graphic novels brings a huge number of variables into play. To my relief and her credit, there was never any question that it could be done. She was one of those people who “got it” upon her first reading of the book, and her desire for others to have that experience kept the entire project buoyant. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to both Teresa and her mighty crew, and I have no doubt that they committed many untold acts of heroism to ensure that Grease Monkey got into bookstores at last.

Phase 5 (here and now)

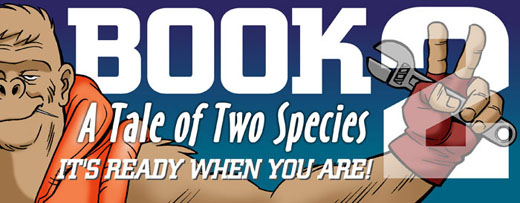

Everything you just read was originally published in Grease Monkey: A Tale of Growing up in Orbit, otherwise known as Book 1. From the first indication of a deal with Tor, it took four years to actually turn it into a real book (which was published in May, 2006). As soon as my feet touched the top of that mountain, I was ready to start on the sequel. It already existed in script form; the ideas hatched during the TV development process had bloomed into that screenplay I wrote in 2000. It was time to decide if I was going to keep it that way and attempt to pitch it as a movie, or go with the far more achievable goal of turning it into Book 2.

Any time you have to team up with other people to get something made, the first requirement is compromise. As the cost goes up, the compromises go up with it. As an active participant in the TV cartoon biz, everything I’d learned on the job told me it wouldn’t end well. Even if the concept had enough juice to catch someone’s eye, there’s no way they’d buy a script and not (ahem) monkey around with it. The thing about working on TV cartoons is that you get a lot of revision notes. Good revision notes improve the material. Bad revision notes just make it different. Guess which kind is more common.

Option A was to submit the script to a process that would probably break my heart. Option B was to keep it to myself and pay it off exactly the way I wanted. When I thought about it that way, it was no contest.

One of the side-benefits of getting Book 1 published by Tor was that they funded a website for it, Greasemonkeybook.com. After it left the launch pad, it was up to me to maintain it on my own time and bucks. As 2006 rolled into 2007, I was in need of some new material to keep the site going, and Book 2 was the obvious way to do it. I’d been drawing a webcomic called Star Blazers Rebirth since 2005, so I had already made the break from paper to pixels. When that project wrapped up in the summer of ’07, I decided Grease Monkey: A Tale of Two Species would take its place.

Unlike Book 1, it was a single story instead of a series of episodes. But rather than draw all 200-plus pages before showing anyone, I decided to break it up into smaller pieces (12-15 pages each) and publish them monthly at the website. This took about two years from start to finish, during which time Book 1 earned a profit, won two awards (see the home page at right), and went to paperback. But Tor expressed no interest in a followup.

Clearly, I was on my own again. But I was used to it. The day job paid the bills and gave me the freedom to NOT turn Grease Monkey into a money-making enterprise. It’s amazing how much pressure that eliminates. When you do something for money, some level of your brain is always quantifying it. Constantly think about how much an hour is worth, or how much you’ll make for drawing a page, is the opposite of creativity. In the worst case, it motivates you only enough to scratch out the bare minimum. You’ll hardly do your best under those conditions; if this experience has taught me anything, it’s that everything you do for love is going to come out better than what you do for money. I love writing and drawing, and I love these characters. That’s enough.

The iteration of Greasemonkeybook.com you’re currently reading is the 2.0 version of the website. With help from the mighty Tom Hakim, it has been upgraded for a cleaner look, a better reading experience, and a stronger platform for future projects. And there will be future projects. After finishing Book 2 in 2009, I returned to the world of Star Blazers to create another webcomic series titled The Bolar Wars Extended. My intention was to start on Grease Monkey Book 3 after that, but another concept has lured me away (keep an eye open for it in 2015). Nevertheless, the full story of Grease Monkey requires a Book 3 and also a Book 4, so they will turn up when the time is right.

Until then, I hope you get to know these characters as well as I do. And don’t be shy about letting me know what you see in them, especially if it’s something unique to you. It’s always nice to get a reminder that Mac and company are out in the wide world making friends of their own.

– Tim Eldred, November 2014